KV Cache, MQA, GQA and Attention!!!!

Purpose Of This Blog

I have been planning to write a blog post on a lot of things I have been reading/playing around with over the past couple of weeks. I explored and tinkered around a lot of core concepts related to LLMs, all of which i’ll try to explain in this blog, a lot of my knowledge of these concepts are consolidated across different but related resources whose link I will provide at the end of the blog.

My goal is to make it much easier to interpret and understand core decisions in Modern LLMs and why are they needed, I will also be diving a bit into the math as well. One thing I have found to help while exploring these concepts is some kind of visualisation, I will put up some of the rough diagrams that I used to interpret the concepts.

Time to dive deep into this stuff then

A Note for the diagrams, my original notes were way messy to be used as a reference, so I tried to make some diagrams that would help the audience gain intuition or visual understanding as to why certain things are happening, These are not professional diagrams, but rather a way to visualise and understand them better.

Overview

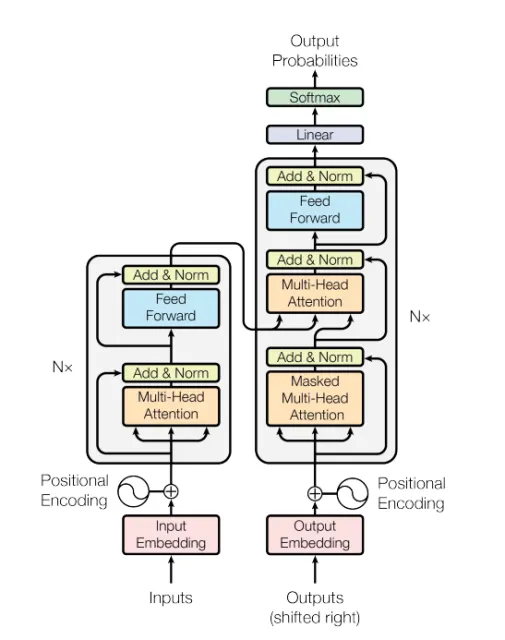

Before I dive into the topics of this blog, I assume the audience who are reading the blog have some kind of pre-req to what LLMs are, what is the transformer architecture, If not I highly recommend going over the following research paper about Transformers.

This is by far one of the most knowledge dense and important papers to understand what was the idea behind Transformers, you don’t just get to learn about the architecture or design of such beatiful models, you get to know the intuition, how every small piece within the architecture plays a big part, there’s so much to transformer than what the bare eyes can see, some of the topics it covers are the following

- Dropout Layers

- Positional + Static Embeddings

- Word Encodings

- FeedForward Layers

- Normalization

- Causal Masked Attention

- MultiHead Attention Vs Single Head Attention

- How the training happens

Attention

There are a lot of moving parts to the architecture, but the focus of this section would be around what is attention, why does it play such a big role in modern LLMs and what is the Math behind it

What is it

Attention is the core module in the transformer architecture that defines relationships between different tokens/words. It accomplishes this through the context of three linear projections applied to the embeddings of the respective tokens: Queries, Keys, and Values.

To understand how attention works, it’s essential to grasp what each of these three components represents:

-

Queries: Queries define which token is actively looking for relationships with other tokens. Think of it as a token asking “What other tokens are relevant to me?”

-

Keys: Keys define what each other token has to offer to the given token. They represent the “offerings” or “capabilities” that other tokens can provide when a query token is looking for relationships.

-

Values: Values define what is the actual information held by that token. While keys and queries help determine the relationship strength, values contain the actual content that gets weighted and aggregated based on those relationships.

Together, these three components allow the attention mechanism to determine which tokens are most relevant to each other and how much information should flow between them, creating the rich contextual understanding that makes transformers so powerful.

Math behind it

To understand how the math works, we first have to understand a couple of things: how the dot products work between different vectors and what they achieve.

Dot products are used most often to find similarity between two vectors or represent them via a score. The higher the dot product, the more similar the vectors are in their respective embedding spaces.

We have three key variables in this picture:

-

attn_weight: The dot product of queries and keys. This represents the raw similarity scores between tokens before any normalization.

-

attn_score: A scaled down version of attn_weight by a factor of the square root of the dimension of key’s embedding vectors (√d_k). This is used to find similarities between the tokens after scaling.

-

context_vector: This is the dot product of attn_score (after softmax) with the values. It represents a simple score of how much context each token has and can be used as a good point to infer the logits.

The attn_score is used to find similarities between tokens. The attn_weight is the unscaled version, and we scale it down because if we multiply queries and keys with variance that is very high, chances are we will get a softmax with very extreme values, thus not giving us correct answers. Scaling it down by a factor of the square root of the dimension of K’s embeddings fixes that by normalizing the variance and preventing the softmax from saturating into extreme values.

Inference

Now that we understand how attention works, let’s explore what happens during inference when a transformer model generates text. This will help us understand why KV Cache is such an important optimization.

During inference, transformers generate text autoregressively—meaning they generate one token at a time, and each new token depends on all the previously generated tokens. Here’s what happens at each generation step:

-

Step 1: Given an initial prompt (e.g., “The cat sat on”), the model processes all tokens in this sequence and generates the next token (e.g., “the”).

-

Step 2: Now with the sequence “The cat sat on the”, the model processes all tokens again (including the newly generated “the”) and generates the next token (e.g., “mat”).

-

Step 3: With “The cat sat on the mat”, the model processes all tokens once more and generates the next token, and so on.

The critical inefficiency here is that at each step, the model recalculates the Queries, Keys, and Values for every single token in the sequence, even though most of them haven’t changed!

For example, when generating the second token:

- The Keys and Values for “The”, “cat”, “sat”, “on” are exactly the same as they were in Step 1

- Only the new token’s Q, K, V need to be computed

- Yet, the model recalculates K and V for all previous tokens anyway

This means we’re doing a lot of redundant computation. As the sequence grows longer, this inefficiency compounds dramatically—if we have 100 tokens, we’re recalculating K and V for 99 tokens that haven’t changed, plus computing them for 1 new token.

To make matters worse, the computational complexity of attention operations scales as O(n²) with respect to sequence length (n). This quadratic scaling comes from the attention mechanism itself:

- Computing Keys (K) for all n tokens: O(n)

- Computing Values (V) for all n tokens: O(n)

- The attention computation QK^T: O(n²) - creating a matrix of similarities between all token pairs

So at each generation step, we’re not only recalculating K and V for all previous tokens (which is redundant), but we’re also doing it with quadratic complexity. This means that generating longer sequences becomes exponentially more expensive in terms of computation time.

This is precisely the problem that KV Cache solves.

KV Cache

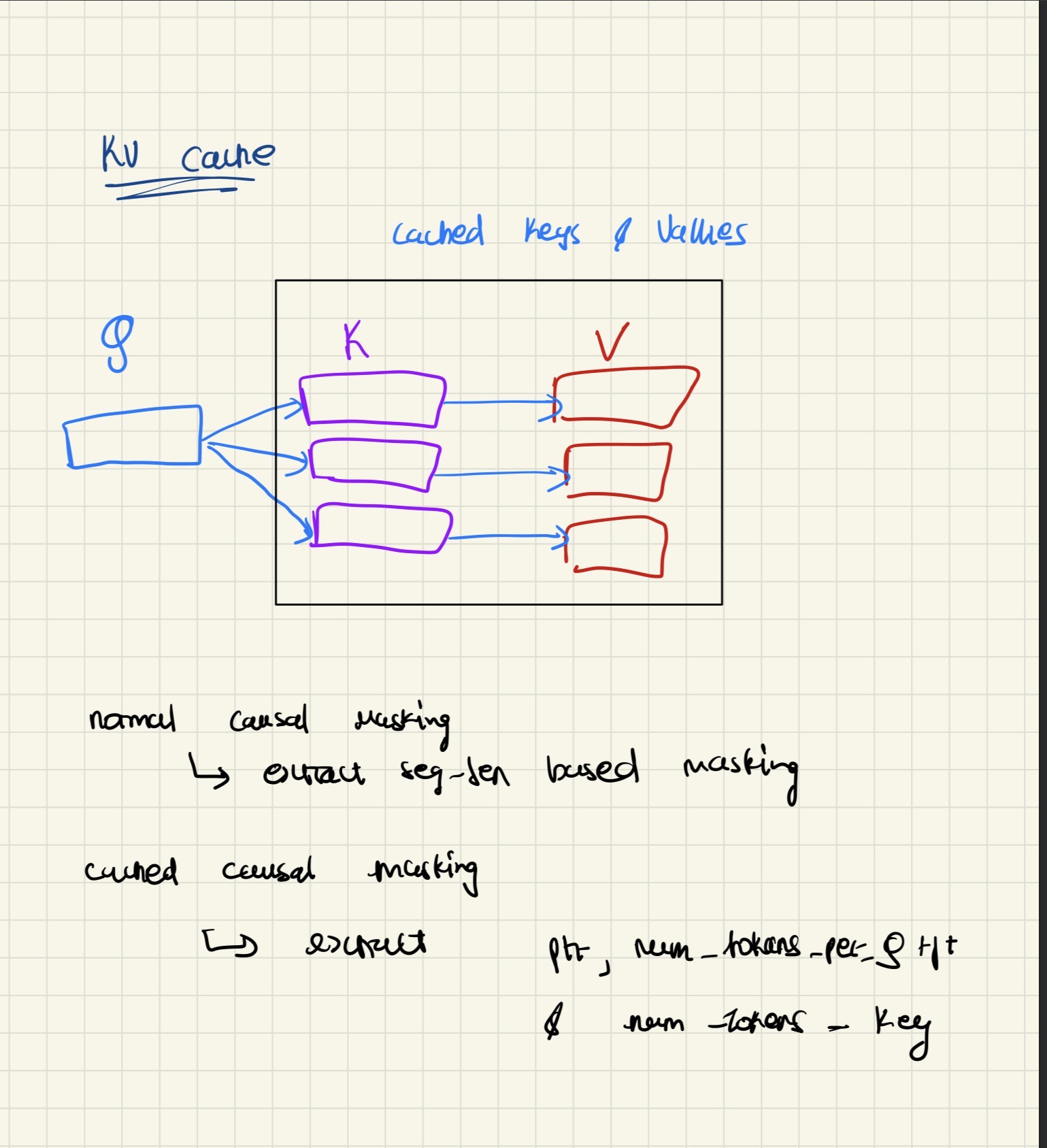

Since we saw the problem above about the quadratic scaling of time complexity of the attention mechanism, we needed something that would solve the issue of recalculation at each step.

So we introduced two new buffers, which are caches for Keys and Values. These buffers store the computed K and V for all previous tokens, eliminating the need to recompute them at every generation step.

How It Works

In our new approach, we calculate the keys and values for all the previous tokens during a new prompt generation and store them in a cache. The cache is refreshed for each new prompt to avoid leading to inconsistent values for the same tokens across different conversations.

Here’s how this changes the generation process:

At Step 1: We pass in the prompt, generate the keys, values, and queries for all tokens in the prompt. We then store the keys and values in the cache, as they will be used later on for subsequent generation steps.

At Step 2 and beyond: When generating a new token, we only compute the Query, Key, and Value for the new token (the one we’re about to generate). We retrieve all previous keys and values from the cache instead of recomputing them.

Complexity Improvement

This fundamentally changes the computational complexity:

-

Without KV Cache: At each step i, we compute K and V for all i tokens. Over n steps, this gives us O(1 + 2 + 3 + … + n) = O(n²) operations just for computing K and V.

-

With KV Cache: We compute K and V for each token only once when it’s first encountered. Over n steps, this gives us O(n) operations for computing K and V—a significant improvement from O(n²).

Note that the attention computation itself (QK^T) still scales as O(n²) at each step, as we need to compute similarities between the new query and all previous keys. However, we’ve eliminated all the redundant computation of K and V for previous tokens, which was a major bottleneck in terms of FLOPs.

Additional Considerations

We also keep track of what position we are in for the query to ensure correct causal masking and correct positional embedding during generation. This is crucial because:

- Causal masking ensures that tokens can only attend to previous tokens (not future ones)

- Positional embeddings need to be applied correctly based on the token’s position in the sequence

The cache also grows linearly with the sequence length, as we store one K and V vector for each token that has been processed. This is a memory trade-off that we accept in exchange for the significant computational savings.

Implementation Details

When implementing KV Cache, there are several important technical considerations to keep in mind:

1. Cache Buffers and Position Tracking

We create two buffers: cache_k and cache_v. These are not neural network parameters (not nn.Parameters), but rather tensor objects that can be moved between devices (CPU/GPU) and persist across forward passes. Additionally, we maintain a pointer variable called ptr that tracks our current position in the sequence. This pointer is crucial for correctly applying causal masking and managing positional information during generation.

Here’s how we initialize the cache buffers and position tracking in the Multi-Headed Attention module:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class MultiHeadedAttentionWithCache(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, din, dout, num_heads, dropout_ratio, context_length, qkv_bias=False):

super().__init__()

assert dout % num_heads == 0

self.dout = dout

self.num_heads = num_heads

self.d_h = dout // num_heads

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout_ratio)

# Linear projections for Q, K, V

self.W_q = nn.Linear(din, dout, bias=qkv_bias)

self.W_k = nn.Linear(din, dout, bias=qkv_bias)

self.W_v = nn.Linear(din, dout, bias=qkv_bias)

# Causal mask buffer (not a parameter, just a buffer)

self.register_buffer(

"mask",

torch.triu(torch.ones([context_length, context_length]), diagonal=1),

persistent=False

)

# KV Cache buffers - these store the cached keys and values

self.register_buffer(

"cache_k",

None,

persistent=False

)

self.register_buffer(

"cache_v",

None,

persistent=False

)

# Position pointer to track where we are in the sequence

self.ptr_current_pos = 0

self.out_proj = nn.Linear(dout, dout)

2. Splitting Keys and Values Before Caching

One critical implementation detail is to split the keys and values before storing them in the cache. This is essential because:

- In multi-head attention, each attention head operates on separate projections of K and V

- If we store the keys and values before splitting them across heads, the information for each individual head gets lost

- When we later load the cached values, computing attention across different heads requires the split representations

- Since the number of heads is technically a model parameter, we need to preserve the head-specific information in the cache

By splitting K and V into their respective head dimensions before caching, we ensure that each head can correctly access its cached information during subsequent generation steps.

Here’s the forward method that implements the KV cache logic:

def forward(self, x, use_cache=False):

batch, seq_len, din = x.shape

# Compute Q, K, V projections

Q: torch.Tensor = self.W_q(x)

K: torch.Tensor = self.W_k(x)

V: torch.Tensor = self.W_v(x)

# Split into heads and transpose for attention computation

# Shape: (batch, num_heads, seq_len, d_h)

Q_new = Q.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_heads, self.d_h).transpose(1, 2)

K_new = K.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_heads, self.d_h).transpose(1, 2)

V_new = V.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_heads, self.d_h).transpose(1, 2)

# KV Cache logic: store K and V after splitting into heads

if use_cache:

if self.cache_k is None:

# First time: initialize cache with current K and V

self.cache_k, self.cache_v = K_new, V_new

else:

# Subsequent times: concatenate new K and V to existing cache

self.cache_k = torch.cat([self.cache_k, K_new], dim=2)

self.cache_v = torch.cat([self.cache_v, V_new], dim=2)

# Use cached K and V (includes all previous tokens + current)

K, V = self.cache_k, self.cache_v

else:

# No cache: use current K and V only

K, V = K_new, V_new

3. Causal Masking with Cache

When applying the causal mask during generation, we need to carefully extract the relevant portions of queries and keys:

- For queries: Extract

ptr:ptr+num_q_tokens- this gives us only the row(s) for the current query token(s) we’re processing - For keys: Extract

:num_tokens_k- this gives us all the keys with which the current query will interact (all previous tokens plus the current one)

This selective extraction ensures that we’re only computing attention scores between the new query token and the appropriate previous tokens, maintaining the causal property of the attention mechanism.

Here’s how we compute attention with proper causal masking when using the cache:

# Compute attention scores: Q @ K^T

attn_score: torch.Tensor = Q_new @ K.transpose(2, 3)

num_tokens_q = Q_new.shape[-2] # Number of query tokens (usually 1 during generation)

num_tokens_k = K.shape[-2] # Number of key tokens (all previous + current)

# Apply causal mask based on whether we're using cache

if use_cache:

# Extract the relevant portion of the mask for current position

attn_score = attn_score.masked_fill(

self.mask.bool()[

self.ptr_current_pos:self.ptr_current_pos + num_tokens_q,

:num_tokens_k

],

-torch.inf

)

# Update position pointer for next iteration

self.ptr_current_pos += num_tokens_q

else:

# Standard causal masking without cache

attn_score = attn_score.masked_fill(

self.mask.bool()[:num_tokens_q, :num_tokens_k],

-torch.inf

)

# Apply softmax to get attention weights

attn_weight: torch.Tensor = torch.softmax(

(attn_score / (K.shape[-1] ** 0.5)), dim=-1

)

# Compute context vector: attention weights @ values

context_vector = attn_weight @ V

# Reshape back: (batch, seq_len, dout)

context_vector = context_vector.transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view(

batch, seq_len, self.dout

)

# Final output projection

logits = self.out_proj(context_vector)

return logits

def reset_cache(self):

"""Reset the KV cache and position pointer for a new sequence"""

self.cache_k = None

self.cache_v = None

self.ptr_current_pos = 0

4. Positional Embedding Tracking

During generation, positional embeddings need special handling:

- Previously: We would generate positional embeddings from position 0 to the end of the sequence length

- With KV Cache: We need to maintain a separate pointer that tracks positional embeddings from the current position to the extracted token length (which is usually 1 for single-token generation)

This is necessary because each new token needs positional embeddings relative to its position in the growing sequence, not relative to the start of the original prompt. The pointer helps us correctly apply positional encodings to new tokens as they’re generated.

Supporting Components

Before we can build the complete transformer model with KV cache, we need a few supporting components:

Layer Normalization:

class LayerNormalization(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, emb_dim):

super().__init__()

# Learnable scale and shift parameters

self.scale = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(emb_dim))

self.shift = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(emb_dim))

self.eps = 1e-5

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor):

# Compute mean and variance along the last dimension

mean = x.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = x.var(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

# Normalize: (x - mean) / sqrt(var + eps)

normalized = (x - mean) / torch.sqrt(var + self.eps)

# Apply learnable scale and shift

return self.shift + normalized * self.scale

GELU Activation Function:

class GELU(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def forward(self, x):

# GELU approximation: 0.5 * x * (1 + tanh(sqrt(2/π) * (x + 0.044715 * x^3)))

return 0.5 * x * (1 + torch.tanh(

torch.sqrt(torch.tensor(2.0 / torch.pi)) *

(x + 0.044715 * torch.pow(x, 3))

))

Feed Forward Layer:

class FeedForwardLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, emb_dim):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(emb_dim, 4 * emb_dim), # Expand

GELU(), # Activation

nn.Linear(4 * emb_dim, emb_dim) # Contract

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.layers(x)

Complete Transformer Block

Now we can build a complete transformer block that uses our KV cache-enabled attention:

class TransformerBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.attn = MultiHeadedAttentionWithCache(

din=cfg["emb_dim"],

dout=cfg["emb_dim"],

context_length=cfg["context_length"],

num_heads=cfg["num_heads"],

dropout_ratio=cfg["dropout_ratio"],

qkv_bias=False

)

self.ff = FeedForwardLayer(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.norm1 = LayerNormalization(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.norm2 = LayerNormalization(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(cfg["dropout_ratio"])

def forward(self, x, use_cache=False):

batch, seq_len, din = x.shape

# Pre-norm attention with residual connection

shortcut_x = x

x = self.norm1(x)

x = self.attn(x, use_cache=use_cache)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = shortcut_x + x # Residual connection

# Pre-norm feedforward with residual connection

shortcut_x = x

x = self.norm2(x)

x = self.ff(x)

x = self.dropout(x)

x = shortcut_x + x # Residual connection

return x

Complete GPT Model with KV Cache

Finally, here’s the complete GPT model that integrates KV cache with positional embedding tracking:

class GPTModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

# Stack of transformer blocks

self.trf_block = nn.ModuleList([

TransformerBlock(cfg) for _ in range(cfg["block_num"])

])

# Token and positional embeddings

self.tok_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["vocab_size"], cfg["emb_dim"])

self.pos_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["context_length"], cfg["emb_dim"])

# Output layers

self.final_norm = LayerNormalization(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.out_proj = nn.Linear(cfg["emb_dim"], cfg["vocab_size"])

# Position tracking for KV cache

self.current_pos = 0

def forward(self, x, use_cache=False):

batch, seq_len = x.shape

# Token embeddings

token_emb = self.tok_emb(x)

# Positional embeddings with cache-aware positioning

if use_cache:

# During generation: use current position to current_pos + seq_len

positions = torch.arange(

self.current_pos, self.current_pos + seq_len,

device=x.device

)

self.current_pos += seq_len

else:

# During training: use positions 0 to seq_len

positions = torch.arange(0, seq_len, device=x.device)

pos_embs = self.pos_emb(positions)

# Combine token and positional embeddings

x = token_emb + pos_embs

# Pass through transformer blocks

for blk in self.trf_block:

x = blk(x, use_cache=use_cache)

# Final normalization and projection to vocab size

x = self.final_norm(x)

logits = self.out_proj(x)

return logits

def reset_kv_cache(self):

"""Reset KV cache and position for all transformer blocks"""

for blk in self.trf_block:

blk.attn.reset_cache()

self.current_pos = 0

Note on Production Implementations

The implementation and concepts I’ve discussed here are designed to provide a clear understanding of what KV Cache is and how it works conceptually. However, in production environments, some additional optimizations are typically made to this approach:

-

Sliding Window Attention: To limit the context window for KV values, production systems often implement sliding window attention, which maintains only a fixed-size window of recent tokens in the cache rather than storing all tokens indefinitely.

-

Pre-allocating Cache Space: Rather than allocating cache space during every operation, production implementations pre-allocate the cache space upfront, which reduces memory allocation overhead and improves performance.

These production optimizations are important for scaling KV Cache to handle very long sequences efficiently. I’ll cover these advanced techniques in detail in a future blog post.

The Memory Bandwidth Bottleneck

KV Cache was initially implemented as a way to save and optimize the performance of recomputing keys and values that were already being computed, thus saving us FLOPs (Floating Point Operations). This was a significant improvement, as we eliminated redundant computation.

However, after implementing KV Cache, it was realized that FLOPs wasn’t the majority of the issue. Rather, another critical factor played a much bigger role: memory bandwidth.

The Problem

Even though we’re caching the keys and values, at each generation step we still need to load them from memory to compute attention. The memory bandwidth problem becomes apparent when we consider the scale of this operation:

- For each layer: Keys and values need to be loaded

- For each head: Multi-head attention requires separate K and V for each head

- For each token in the sequence: We need to load K and V for all previous tokens

- Twice the data: We’re loading both Keys and Values

This means we’re reading massive amounts of data from memory at every single generation step. As sequences grow longer and models have more layers and heads, the memory bandwidth requirements become the primary bottleneck, not the computational FLOPs.

The Discovery

The key insight was that GPUs can handle more FLOPs than the data bus can supply to them. In other words, the GPU’s computational units are often sitting idle, waiting for data to be loaded from memory. This is a classic memory-bound problem—the hardware is compute-rich but memory-poor.

This realization led to the development of Multi-Query Attention (MQA) and Grouped-Query Attention (GQA), which are techniques specifically designed to optimize memory bandwidth by reducing the amount of K and V data that needs to be loaded and stored, while maintaining the quality of the attention mechanism.

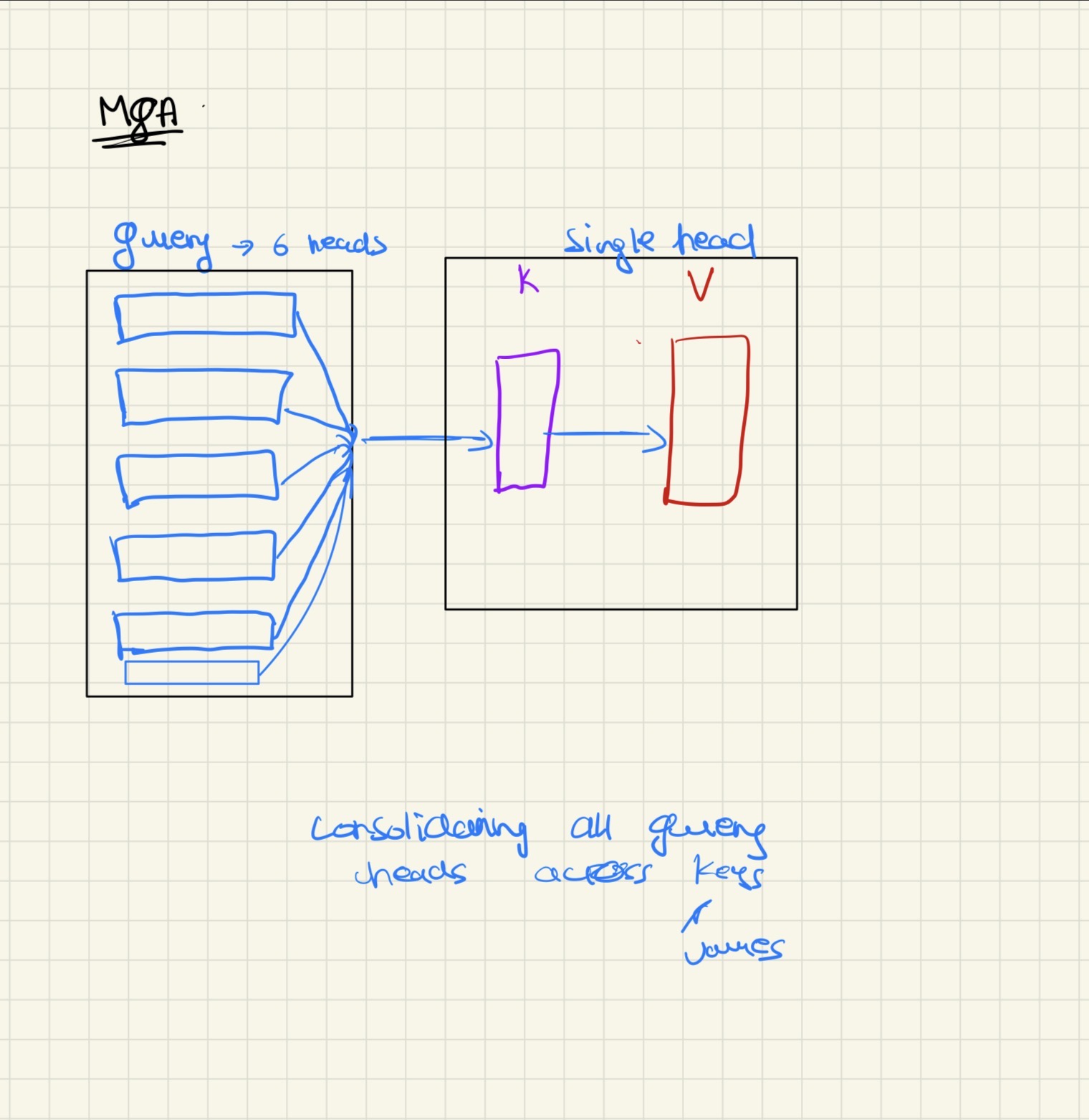

MQA

Now, the idea of MQA (Multi-Query Attention) and how it works is pretty simple. To understand it, let’s recall the definitions of attention components from earlier:

Queries are the ones that drive the representation power of what a token is actually looking for. This is largely the factor that captures different semantic relationships between tokens. Collapsing the heads on this particular projection wouldn’t make sense, as we’d lose the ability to model diverse relationships.

Keys and Values, on the other hand, are the major contributors towards the memory bandwidth issue. Practically speaking, these are the variables whose dimensions should be collapsed to reduce memory bandwidth requirements.

How MQA Works

MQA works by limiting the number of heads for keys and values to just one, while keeping multiple heads for queries. This means:

- Queries (Q): Still have multiple heads (e.g., 8, 16, or 32 heads) to maintain representation power

- Keys (K): Reduced to a single head, shared across all query heads

- Values (V): Reduced to a single head, shared across all query heads

By doing this, we avoid loading keys and values for different heads again and again. Instead of loading separate K and V for each head, we load them once and reuse them across all query heads. This dramatically reduces memory bandwidth requirements.

The Trade-off

However, this optimization comes with a downside: we are limiting our representation capabilities for keys and values to just one head. This leads to a downgrade in the performance capabilities of the trained model itself, just because it isn’t able to capture the relationships that it used to in Multi-Head Attention (MHA) due to having more heads for both keys and values.

In standard MHA, different heads can learn to attend to different types of relationships (syntactic, semantic, positional, etc.) through both queries and keys. By reducing K and V to a single head, we lose some of this diversity in how relationships are represented, which can impact model quality.

Implementation

The implementation for MQA is pretty simple. The key detail is that we need to match the per-head dimension of queries to the dimension of the single head key and values.

For example, if we have:

num_headsquery heads, each with dimensiond_k- A single key head with dimension

d_k - A single value head with dimension

d_v

Then each query head’s dimension must match the key dimension (d_k) for the attention computation QK^T to work correctly. Apart from this dimension matching requirement, the implementation is similar to standard Multi-Head Attention (MHA).

The main change is in how we project and reshape the tensors:

- Queries are projected and split into multiple heads (as in MHA)

- Keys and Values are projected but kept as single heads (not split)

- During attention computation, each query head attends to the same shared key and value heads

Here’s the complete implementation of Multi-Query Attention:

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class MultiQueryAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, din, dout, num_heads, dropout_ratio, context_length, qkv_bias=False):

super().__init__()

assert dout % num_heads == 0

self.dout = dout

self.num_heads = num_heads

self.head_dim = dout // num_heads # Dimension per query head

self.dkv = self.head_dim # Dimension for single K and V head (must match head_dim)

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout_ratio)

# Causal mask buffer

self.register_buffer(

"mask",

torch.triu(torch.ones([context_length, context_length]), diagonal=1)

)

# Projections: Q has full dout dimension, K and V have only dkv dimension

self.Wq = nn.Linear(din, dout, bias=qkv_bias) # Multiple heads for Q

self.Wk = nn.Linear(din, self.dkv, bias=qkv_bias) # Single head for K

self.Wv = nn.Linear(din, self.dkv, bias=qkv_bias) # Single head for V

self.out_proj = nn.Linear(dout, dout)

def forward(self, x):

batch, seq_len, din = x.shape

# Compute Q, K, V projections

Q = self.Wq(x) # Shape: (batch, seq_len, dout)

K = self.Wk(x) # Shape: (batch, seq_len, dkv) - single head dimension

V = self.Wv(x) # Shape: (batch, seq_len, dkv) - single head dimension

# Reshape Q into multiple heads: (batch, num_heads, seq_len, head_dim)

Q = Q.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_heads, self.head_dim).transpose(1, 2)

# Expand K and V to match Q's head structure

# We unsqueeze to add head dimension, then expand to match num_heads

# This creates copies of the single K/V head for each Q head

K = K.unsqueeze(1).expand(batch, self.num_heads, seq_len, self.dkv)

V = V.unsqueeze(1).expand(batch, self.num_heads, seq_len, self.dkv)

# Compute attention scores: Q @ K^T

# Shape: (batch, num_heads, seq_len, seq_len)

attn_score = Q @ K.transpose(2, 3)

# Apply causal mask

attn_score = attn_score.masked_fill(

self.mask.bool()[:seq_len, :seq_len],

-torch.inf

)

# Compute attention weights with scaling

attn_weight = torch.softmax(

attn_score / (K.shape[-1] ** 0.5),

dim=-1

)

attn_weight = self.dropout(attn_weight)

# Compute context vector: attention weights @ values

context_vector = attn_weight @ V

# Reshape back: (batch, seq_len, dout)

context_vector = context_vector.transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view(

batch, seq_len, self.dout

)

# Final output projection

logits = self.out_proj(context_vector)

return logits

Key Implementation Details

1. Dimension Matching:

The critical requirement is that dkv (the dimension of the single K/V head) must equal head_dim (the dimension of each Q head). This ensures that the matrix multiplication Q @ K^T works correctly, as each query head’s dimension matches the key dimension.

2. Tensor Expansion:

After projecting K and V to their single-head dimensions, we use unsqueeze(1) to add a head dimension, then expand() to broadcast this single head across all num_heads. This creates the illusion of multiple K/V heads while actually storing only one set of keys and values in memory.

3. Memory Efficiency:

The key advantage is that we only store and load one set of K and V tensors (each of dimension dkv) instead of num_heads sets. This reduces memory bandwidth by a factor of num_heads compared to standard Multi-Head Attention.

GQA

Since we talked about how there was a downgrade in the performance/capabilities of the model that used MQA, a new type of attention came to help with it, which is Grouped Query Attention (GQA).

The Intuition

The idea/intuition behind Grouped Query Attention is pretty similar to what we wanted in the first place from MQA, but with lower performance downgrade and performance similar to what MHA returns, but not at the expense of optimizing memory bandwidth.

The key concept is: rather than limiting K and V to just a single head (as in MQA), we divide them into groups so that we can capture more representation between K, V and Q, but at the same time limiting our memory bandwidth usage.

In this approach, a set of Q heads attend to a single group of K and V. This creates a middle ground between MHA (where each Q head has its own K and V) and MQA (where all Q heads share a single K and V).

Implementation

The implementation or approach can be divided into the following steps:

1. Decide on the number of heads and groups

First, decide on num_heads and num_groups. The deciding factor should also obey the rule that:

Otherwise, we won’t be able to split the Query set into different groups of K and V evenly.

2. Split queries and group keys/values

Split the query into heads (as in standard MHA), and then split K and V into different groups. One of the key factors for deciding the dimensions d_kv and d_q for this approach is using the following formulas:

3. Create group_heads variable

Create a variable called group_heads, which defines how many heads each group gets:

4. Create a buffer to track head-to-group mapping

Now create a buffer that keeps track of which heads get which group of K and V. This is kind of like an index range whose formula is the following:

This defines which heads belong to which groups. This buffer should be used when calculating the attention computation to ensure each query head attends to the correct group of keys and values.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class GroupedMultiQueryAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, din, dout, num_heads, dropout_ratio, context_length, num_groups, qkv_bias=False):

super().__init__()

assert dout % num_heads == 0

assert num_heads % num_groups == 0

self.num_groups = num_groups

self.num_heads_per_group = num_heads // num_groups

self.dout = dout

self.num_heads = num_heads

self.head_dim = dout // num_heads

self.dkv = self.head_dim

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(dropout_ratio)

# Causal mask buffer

self.register_buffer(

"mask",

torch.triu(torch.ones([context_length, context_length]), diagonal=1)

)

# Buffer to map each head to its corresponding group

self.register_buffer(

"head2group",

torch.arange(num_heads) // self.num_heads_per_group

)

# Projections: Q has full dout, K and V have num_groups * dkv

self.Wq = nn.Linear(din, dout, bias=qkv_bias)

self.Wk = nn.Linear(din, self.num_groups * self.dkv, bias=qkv_bias)

self.Wv = nn.Linear(din, self.num_groups * self.dkv, bias=qkv_bias)

self.out_proj = nn.Linear(dout, dout)

def forward(self, x):

batch, seq_len, din = x.shape

# Compute Q, K, V projections

Q = self.Wq(x)

K = self.Wk(x)

V = self.Wv(x)

# Reshape Q into multiple heads: (batch, num_heads, seq_len, head_dim)

Q = Q.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_heads, self.head_dim).transpose(1, 2)

# Reshape K and V into groups: (batch, num_groups, seq_len, dkv)

K = K.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_groups, self.dkv).transpose(1, 2)

V = V.view(batch, seq_len, self.num_groups, self.dkv).transpose(1, 2)

# Map each query head to its corresponding K/V group

Kh = K[:, self.head2group, :, :]

Vh = V[:, self.head2group, :, :]

# Compute attention scores: Q @ K^T

attn_score = Q @ Kh.transpose(2, 3)

# Apply causal mask

attn_score = attn_score.masked_fill(

self.mask.bool()[:seq_len, :seq_len],

-torch.inf

)

# Compute attention weights with scaling

attn_weight = torch.softmax(

attn_score / (K.shape[-1] ** 0.5),

dim=-1

)

attn_weight = self.dropout(attn_weight)

# Compute context vector: attention weights @ values

context_vector = attn_weight @ Vh

# Reshape back: (batch, seq_len, dout)

context_vector = context_vector.transpose(1, 2).contiguous().view(

batch, seq_len, self.dout

)

# Final output projection

logits = self.out_proj(context_vector)

return logits

The Result

Thus, this leads to Grouped Query Attention, which is:

- Better in terms of performance than MQA - because it maintains more representation diversity through multiple groups

- Still a bit less than MHA - because it doesn’t have full head diversity for K and V

- Bandwidth optimization is far better than MHA - because we’re loading fewer K and V groups than full heads

GQA provides an excellent trade-off between model performance and memory bandwidth efficiency, making it a popular choice in many modern LLMs.

Math Behind Optimization

The math behind the optimization is pretty simple to understand once the memory concepts are clear. Let’s break down the memory bandwidth requirements step by step.

Memory Bandwidth Formula

When loading keys and values from memory, we need to account for several factors:

- We are loading two modules: K and V, so we have a factor of 2

- We are loading them for heads (number of key/value heads)

- We are loading dimensions for each head

- We are doing this for layers

- We are doing this for each token of sequence length

- We are using bytes per element, depending on precision:

- FP16: 2 bytes

- FP32: 4 bytes

- FP64: 8 bytes

So the formula for memory bandwidth is:

Or more compactly:

Memory Scales Linearly with Number of Heads

From the formula above, we can see that memory bandwidth scales linearly with the number of heads . This is why reducing the number of key/value heads has such a significant impact on memory bandwidth.

MQA Memory Reduction

In Multi-Query Attention (MQA), since the number of heads is reduced to 1:

The complexity is reduced by a factor of:

Where is the number of heads in MQA (which is 1).

For example, if we started with heads in standard MHA, MQA reduces the memory bandwidth by a factor of 32.

GQA Memory Reduction

In Grouped Query Attention (GQA), the complexity is reduced by a factor of:

Where is the number of groups.

For example, let’s say our number of groups is and we started with heads. The memory bandwidth is reduced by a factor of:

So GQA provides an 8x reduction in memory bandwidth compared to standard MHA, while still maintaining better representation capabilities than MQA (which has a 32x reduction but with only 1 head).

Comparison Summary

To summarize the memory bandwidth reduction:

- Standard MHA: Full memory bandwidth (factor of 1)

- GQA (with , ): Reduced by factor of 8

- MQA (with ): Reduced by factor of 32

This mathematical analysis clearly shows why these attention variants are crucial for efficient inference, especially as models scale to longer sequences and more layers.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we’ve explored the fundamental concepts that power modern LLM inference: from the basic attention mechanism, through KV Cache optimization, to the memory-efficient attention variants of MQA and GQA.

Understanding these internals is crucial for anyone working with large language models, whether you’re optimizing inference performance, building production systems, or simply trying to understand how these powerful models actually work under the hood.

The journey from standard Multi-Head Attention to these optimized variants demonstrates a key principle in systems design: identifying the real bottleneck (memory bandwidth, not just FLOPs) and finding the right trade-offs between model performance and computational efficiency.

All of the code examples in this blog were coded by me via the concepts that I learnt and understood from different resources with some theoretical help from GPT-5. The concepts,code and information have been consolidated from various online resources and textbooks and research papers, with the goal of providing a clear, accessible perspective into what’s happening in the internals of LLMs.

I hope this blog has helped you gain a deeper understanding of these critical optimization techniques. If you have questions or want to discuss these concepts further, feel free to reach out!

Resources

A lot of the information came via a lot of chats with GPT-5 in learning mode and thinking mode, I would highly recommend you to try it out to understand the concepts better.